Print in Focus: Picasso, 'Buste de femme (with dedication plate)'

Buste de femme (with dedication plate) was discovered only recently in the correspondence of Boris Kochno, a Russian poet, who was Sergei Diaghilev’s secretary and lover, and is not recorded by Brigitte Baer in her catalogue raisonné of the graphic works of Pablo Picasso. The etchings are most likely unique and have been authenticated by Administration Picasso.

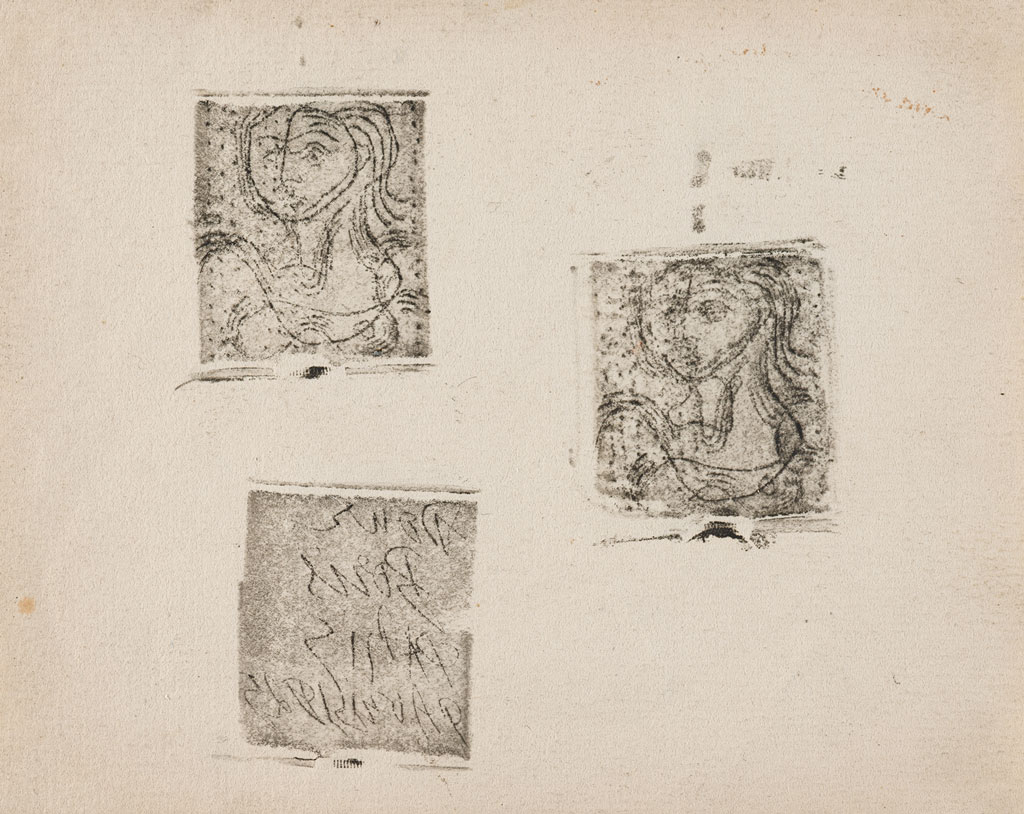

The print is composed of three etchings printed by the artist on a single sheet. Two of the etchings depict the face and bust of a woman and have been printed from the same plate. The third etching, printed from the reverse of the plate, is a dedication reading Pour Boris / Paris / 9 avril 1925.

In the spring of 1925, the Ballets Russes impresario Diaghilev invited Picasso, his wife Olga Khokhlova (a former dancer with the company) and their four-year old son Paulo to come to Monte Carlo to attend a trial run of a new production, Zéphire et Flore, with choreography by Léonide Massine and sets and costumes by Georges Braque. Picasso supplied a drawing of a seated woman for the cover of the souvenir programme. Diaghilev sent his assistant and artistic collaborator, Kochno, to accompany the Picassos from Paris on their train journey. Picasso had met the young Russian poet in 1921, soon after he had been engaged by Diaghilev as his secretary, and had done a portrait drawing of him.

Boris Kochno, Paris, 1921

Pencil on paper

32 x 22cm

On 9 April 1925, the day of the Picassos’ departure for Monaco, Kochno went to the artist’s studio on the rue La Boétie, where Picasso made him a small gift of the present sheet of etchings. With Kochno present, the artist printed the etchings himself on the press that he had been given around 1913 by the printer Louis Fort. Picasso appears to have first considered placing the image on one side of his paper, with the dedication alongside it. However, when the plate was first pulled a slippage of 2-3mm occurred, and Picasso then reprinted the image, which now appears on the upper left. Finally, the reverse of the plate with the inscription Pour Boris / Paris / 9 avril 1925 was printed below it. The paper thus went through the press three times.

Buste de femme (and dedication plate) relates to several of these prints, a number of which were experimental. Some of these, including Tête de femme de face (Baer 89), Femme nue aux traits parallèles (Baer 96, fig. 3), and Tête de femme, face et profil (Baer 240), are executed in a similar fashion to the present etching, with repeated lines emphasizing the contours of the woman’s hair and features of her face, as well as of the body itself. This graphic development seems to have gone forward in parallel with the use of a continuous flowing line to define faces and figures, which can be seen in contemporary prints, drawings and paintings (sometimes scratched into the paint).

The existence of the present work dated April 1925 suggests that some of the related prints date from earlier in 1925 than Baer believed, and that some of Picasso’s ideas may have been worked out in the etchings before the sketchbook drawings. At the same time, two of the prints, which show pairs of dancers (Baer 112-113) and went through various states, were surely done after Picasso’s visit to Monte Carlo (9 April - mid-May 1925), when he made many drawings of members of the ballet company during practice and rehearsal.

Tête de femme, face et profil

Paris, 1925

Scraper on stone covered with lithographic crayon

c. 11.2 x 11.7cm

Although there are no other plates as small as this, it relates to a series of some 35 etchings on zinc plates approximately 121 x 80mm, which Baer suggested the artist might have used as a kind of sketchbook.[i] She thought that they might all date from the end of 1925 and the start of 1926, but in her catalogue she dates them between 1924 and 1926, the majority to the middle and end of 1925, on the basis of similarities to drawings in dated sketchbooks of that period. With a few exceptions, only one proof was pulled by the artist from each of the plates, often on yellowish Ingres paper, with the plates and proofs kept by Picasso, and almost all are now in the Musée Picasso, Paris. Four of the prints (Baer 70, 114-116) bear November 1925 dates.

Buste de femme (and dedication plate) provides an important clue to deciphering the relationship and dating of Picasso’s work in different media at this time. Not only does it have an academic relevance, but it also constitutes a wonderful token of friendship to Kochno.

We would like to thank Marilyn McCully and Michael Raeburn for their assistance in researching the etchings and writing this fascinating story, which unveils the possibility that Picasso may have first used the etching medium as a springboard to his creativity rather than sketches and drawings as briefly evoked by Baer in the first volume of the catalogue raisonné.

[i] “Il est … possible que l’artiste se soit servi de cette série de petits zincs comme d’une sorte de carnet à croquis” (Brigitte Baer, ed. Picasso peintre-graveur (Bernhard Geiser), vol. 1, Berne, 1990, p. 179). The works in question are Baer 70, 72-100, 112-116. As she points out (ibid.), many had been given earlier dates in Geiser’s original edition of the first volume of the catalogue